|

Text and layout © Ed Shum, 2003. Ed Shum asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work |

|

Long Reviews |

|

Value doesn’t have to be expressed in terms of wealth either: consider Leslie’s promise to Maggie - to remember the minute they spent together - causing Maggie to attach emotional value to the memory. The idea that an emotional promise can be a commodity seems strange, but one can see how the consumerism of emotion finds easier expression than the treatment of love as a matter beyond evaluation. Perhaps WKW does believe in love as an ephemeral, value-free concept, but his characters are forever straddling the line between submitting themselves to such an untrammelled belief, but fearing the vulnerability - emotional exposure, possibilities of rejection - that such a concept entails. This suggests that they view the giving of emotion as a limited commodity: so that rejection takes them closer to emotional destitution. This is summed up in the scene where Leslie seeks out his natural mother, who shuns him without even showing herself. Having exposed himself in seeking her, Leslie is rejected - and so his instinctive reaction is to reciprocate this: ‘She wouldn’t even let me see her face... so I wasn’t going to let her see mine.’ |

|

Review of Days Of Being Wild (1990) |

|

|

|

...Continued... [Page 4] |

|

End |

|

The overall result is that the idea of value is both a conspicuous and hard to grasp concept in Days. On the one hand, there are the direct equations/substitutions of value with the ephemeral idea of love - causing one to view the connection with repugnance or suspicion. But on the other hand, WKW allows the subtext of commercialism to colour all the relationships in Days, but in a manner often subtler than our gut instincts can detect. The effect seems to point to how a conception of love as absolute, ephemeral, beyond conceptions of value, is an ideal which is unable to find root in reality. The characters trammel their existences by reference to comforting concepts of value, but - while there is a lot that is sad in Days - this is not a tragedy in itself, as WKW shows how the inherent commercialism of society is not a concept which can be totally divorced from the ‘warm’ idea of love. Is this a good or bad thing? WKW’s position is never clear, which is why his films avoid a partisan viewpoint, but he does acknowledge how the treatment of love as a commodity is uncomfortable, yet somehow inescapable. Consider Takeshi Kaneshiro in Fallen Angels, comparing himself to a ‘shop’, hoping his girlfriend will forever be a customer: the concept is absurd, for the idea of commerce is inherently fickle. Yet, in the end he is dumped, just like a product past its expiry date (to borrow a Chungking concept), suggesting that it is equally absurd to take the idea of love as an absolute, immutable concept beyond value. The end result is Takeshi and the killer’s agent riding off together, but strictly on limited terms - no longer with the ideal of absolute love. WKW’s treatment of this is double-edged: the rejection of absolute love is a shock, but the alternative ‘hopeful’ approach would be to accept obsession and hurt in striving for an unquantifiable ideal. The resultant compromise is simply a mechanism to ensure survival. |

|

Considering this was only WKW’s second film, this is an incredibly assured effort. The style is clearly a departure from many Hong Kong standards, Chris Doyle’s luxurious cinematography giving the details a rich yet impressionistic texture. The look, particularly the interior shots, brings to mind European drama. This is enough for some to see WKW as obsessed with western auteurism - seen as ‘indulgent’ cinema. Yet WKW, taking a cast of popstars and a vision in his head, has created something which bears his unique hallmarks. As a chapter in his career, this is incredibly far removed from his debut, yet one can also spot how he developed after Days. Since Days, he refined his technique and found more succinct ways of expressing concepts, yet managing to reach into more impressionistic territory, finding a method of creating epiphany and uplift. One of Days’s greatest faults, if only in comparison to later WKW, is that it doesn’t have the exhilarating feel of his off-beat mid-90’s hip-fests, or the emotional soar or power of Ashes Of Time or In The Mood For Love. However, stood on its own, it is still an excellent example of marrying concepts to a tale told in stunning fashion. This is still unlikely to woo non-WKW fans, as this film is full of his trademark solipsism, brooding indecision being of more importance than a fast moving plot. The pacing in Days is best described as luxuriant, but perhaps a bit too sedate - the film doesn’t hit you or carry you off, but asks you to think and perhaps, slowly, empathise. |

|

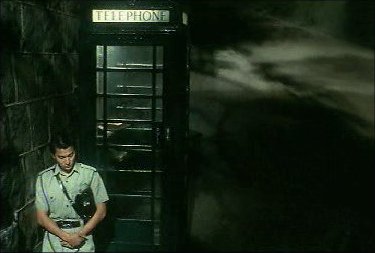

A waiting game: the nascent connection between Maggie and Andy ends prematurely, and with questions as to what the nature of the connection was. This is reflected in the ambiguity of Andy’s outlook: whilst he is prepared to wait momentarily at the phonebox, he cannot invest his hopes on anything more concrete |

|

Compared to later WKW, Days is both simple yet also complex. Premises present themselves as relying more on archetype than later films. Notably, control of actors varies: Leslie gives a masterful and complex performance which dominates the screen, but Maggie’s role is slightly too subdued - not moving far enough from her simple ‘secondary’ role in As Tears Go By. By contrast, Carina’s ‘brassy’ performance is so noisy that she seems out of kilter with the other characters. WKW devotes quite some time to her relationship with Leslie, but this cycle of short term fulfilment seems disjointed, and so the audience don’t empathise well here. The story is allowed to jump from relationship to relationship, and so this adds a degree of complexity, but also detracts from the viewer finding a ‘meaningful’ relationship. In the end, WKW stops the tale becoming too disordered by concentrating on the core of Leslie’s actions, and then relocating the focus to his birthroots, his formation. In this sense, WKW shows his ability to accurately locate an acute emotional point to delve into his characters - something which he has honed in later films. |

|

Technically, the film manages to marry ‘arthouse’-flavoured techniques with a richness which is as far from amateur as possible. As mentioned before, cinematography is classy, although not as exciting as Chris Doyle’s later contributions. William Chang’s production design is also excellent, evoking a Hong Kong which many had forgotten. WKW’s angle is to turn the territory into a depopulated zone of near stasis - characters looped into their pasts, like Andy’s cop, walking the same streets. Musically, the film’s latinized beats sporadically turn up, suggesting slow, somehow fatalistic dances. This theme merges the uncertainty of youth with an idea of moving to a rhythm, something which can be followed and divined, the beauty being the movement rather than the destination. |

|

And that seems to sum Days up: WKW finds beauty in the execution of the conceits contained, but the destination seems doom-laden. Compared to his later films, the sense of epiphany is lesser, and there are fewer thrills, leaving us to admire the film and think rather than actively engage at an emotional level. Having said this, it is still an excellent film in general - better than the work of many other directors at their best. Seen thus, it would be fair to say that, for another director, Days would be their crowning masterpiece, their magnum opus, but for WKW it was only a promise of what was to come. |

|

The holy trinity: WKW, Chang and Doyle’s techniques shine through in a fashion which is both polished and unjaded. Even those who didn’t like the film admired its production values. In later films, WKW would marry technique to emotion even more effectively |

|

Page: |

|

Page: |