Returning to the concept of the canned pineapples, this shows Takeshi’s denial yet again. For some viewers, such denial is unforgivable; worthy of condemnation - but WKW revels in showing us the lengths his character will go to. Shorn of his girlfriend, Takeshi is left with the shards of what amounts to her identity. But how, one may ask, does a penchant for pineapples constitute an identity? WKW lets Takeshi dwell, in an oblique way, on the absurdity of such a concept. And the idea of absurdity strikes us as we see Takeshi buying more and more out of date canned pineapples whilst building up to his self-appointed deadline. But this absurdity is used to reach a very profound point which WKW seems to be making: that there is no other way of expressing the place May has in Takeshi’s heart; the identity he has given her within himself. There are no absolute concepts he can refer to that would convey his feelings. Just as identity has been portrayed via relative concepts, emotion must too. Not because it is unimportant, not because it is not unique and everyone is in the same boat (the concept which many critics wanted WKW to expand on in In The Mood For Love). But simply because, though he does seem an absolutist romantic, Takeshi cannot rely on absolute concepts - he is surrounded by consumables, or the idea of disposability (like the outlook of the Midnight Express’s boss). His pager password is ‘I love you for ten thousand years’ - and while this concept may seem wildly ethereal, it too is limited, merely a relative measure of time.

|

It doesn’t take too much for one to analyse such a concept in relation to Hong Kong itself. A love limited to ten thousand years - just another lease in a land built on leases. And after that? The future remains uncertain. Returning to Takeshi, we return to the present. As Brigitte tells us: ‘Someone who likes pineapples today may not like pineapples tomorrow. People will change.’ Yet for Takeshi, it is a concept which has become ingrained in his mind - a connection which makes up his own identity even when the external facts have changed. Compare Tony Leung Kar-Fei in Ashes Of Time when he tells us that all he remembers is his love of peach blossoms - it is a characteristic of himself because it connects him to the memories that make him who he is.

|

In the end, Takeshi can no longer deny the external truth - that May is now only in his past. In a moment of classic psychological projection, he consumes all the unwanted, rejected cans of pineapple that signify his love. This is a simultaneous last-ditch attempt to bring these symbols within himself, the symbol being a substitute for the real person, as well as being an inevitable rejection, given that his body will not take such an extreme. In desperation, he goes to the Midnight Express stall to seek out the other May - all we know of her is her name, and so it is obvious that again Takeshi is seeking a symbolic substitute. And again he is unsuccessful.

|

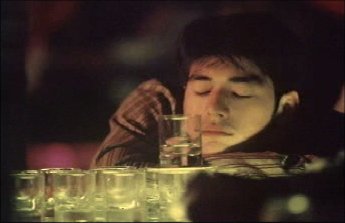

What follows is a classic study of Takeshi’s very identity. Whilst it may seem like he is merely wallowing as he calls just about every woman he has ever known, we find him bringing each of his memories - identifiers of his personal identity - to the surface. And each is cruelly destroyed by reality. His body then throws up the pineapples, the belated rejection as he purges himself of May (and the personal identity he has carved out for her) whom he vows never to go out with again.

|

Time for a new start, or at least that is the impression we get from Takeshi. This is the moment he meets Brigitte again. By our understanding of convention, we see his move as a rebound. Yet there is something undeniably fresh about their meeting: him incessantly asking questions, her invariably ignoring him. As yet he knows nothing of her - she isn’t a part of his history. His first words show the very cosmopolitan nature of Hong Kong - he tries to know her, but he doesn’t even know what language she speaks, so he repeats his question in four languages. They find a common tongue (Takeshi’s face lighting up as he tells of his Taiwanese roots) yet Brigitte gives nothing away.

|

At the very least, if nothing more, they share a room for the night. They share physical space in the same way that so many individuals share the geography of Hong Kong. She sleeps whilst he is awake. They pass time. And they part. This time Takeshi has no relative values to play with - no personal traits which he can hold as her identity with layered emotional meanings. All he can be sure of is that she is a pretty woman in a wig - who should have clean shoes. And what can he take away from that? What memory is that? In the end, it is her small act of requiting his presence - by giving him the happy birthday message, that forms something which he can treasure - a requited memory to identify her by.

|